A large body of research already exists confirming the expected – children living in affordable and stable housing are more likely to have better outcomes in life, including but not limited to, performing better academically, having fewer behavioral or health problems and experiencing fewer mental health issues. Recent research, however, has begun to dig past the long-known benefits of affordable housing for children to explore the actual pathways that connect housing affordability and instability with outcomes for children.

For example, while a January 2022 Journal of Youth and Adolescence study found that housing insecurity has a direct association with future behavioral problems,i the research also noted that “it is possible alternate mechanisms link housing insecurity with adolescent behavior problems.” A few months later, in March 2022, The Review of Educational Research investigated some of those alternate mechanisms by which housing impacts children as elicited by its review of 64 studies published between 2000 and 2020.ii

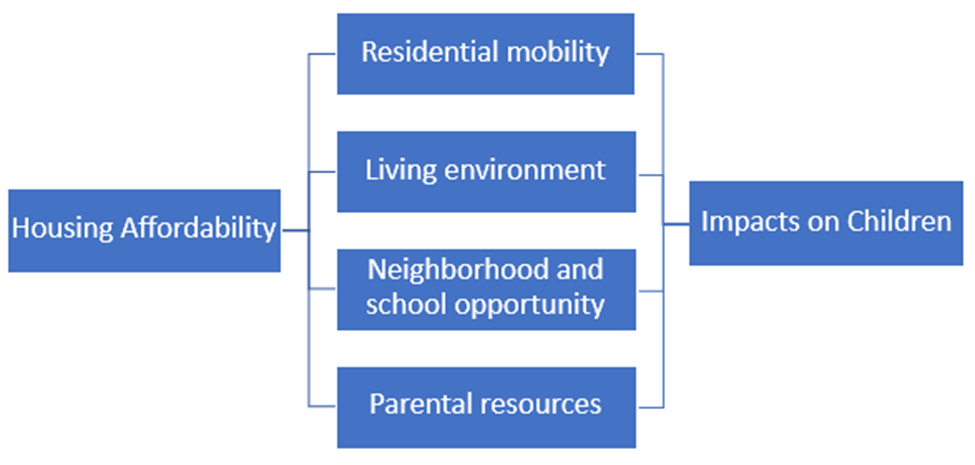

This review explored four theoretical pathways connecting housing affordability with childhood well-being: (1) the residential mobility pathway, (2) the living environment pathway, (3) the neighborhood and school opportunity pathway and (4) the parental resources pathway. Figure 1 below provides a visual of these indirect mechanisms.

The first two pathways, “residential mobility” and “living environment,” showed the most evidence connecting housing unaffordability with negative childhood outcomes such as lower academic achievement, mental health issues and behavioral issues. Housing affordability issues are connected to increased residential mobility, such as changing schools, homelessness and more frequent moving. In short, when a family is forced to move often due to housing unaffordability, children are more likely to experience negative outcomes.

Similarly, housing affordability issues were linked to greater risk associated with a child’s living environment. When housing is unaffordable, children are more likely to live in housing with crowding and poor conditions. Unsurprisingly, children living in these scenarios are also more likely to experience negative outcomes.

The third pathway, “neighborhood and school opportunity,” and the fourth pathway, “parental resources,” have less clear evidence in the literature. Regarding the third, while living in higher poverty neighborhoods and attending lower quality schools are linked with negative outcomes for children, traditional research methodology, such as looking at whether a family is housing cost-burdened, fail to adequately analyze these impacts.

Nevertheless, the research still supports the premise that lack of affordable housing options can limit where families and children live, increasing their likelihood of moving into high-poverty neighborhoods and negatively impacting long-term earnings prospects, educational attainment and access to high-quality schools.

While the final pathway, parental resources, is less well-studied, some research exists supporting the framework that child outcomes are negatively impacted by parents who have less financial resources to spend on childhood enrichment.

Even with limited research, available studies do make clear that a lack of safe, stable and affordable housing negatively impacts children in multitudinous ways.

For more information on the benefits affordable housing provides to children, as well as for the economy, communities, education and health, check out the NC Housing Finance Agency’s Benefits of Housing reports.

_____________________________________________

i Marçal, K. Pathways from Food and Housing Insecurity to Adolescent Behavior Problems: The Mediating Role of Parenting Stress. Journal of Youth and Adolescence 51, 614–627 (2022). https://doi.org/10.1007/s10964-021-01565-2

ii Holme, J. J. Growing Up as Rents Rise: How Housing Affordability Impacts Children. Review of Educational Research, 92(6), 953–995 (2022). https://doi.org/10.3102/00346543221079416